Block the Vodafone - Three merger

This is a longer version of an article just published on LinkedIn.

We’ve sent a submission to the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), urging it to block a proposed merger between the UK’s Vodafone and Three.

The CMA has until March 22 to decide whether or not to conduct a full investigation and, we hope, eventually block it. Lessons from this proposed deal can be applied across countries.

Mergers like this are bad news: a freight train of independent international evidence shows that they mean higher prices for consumers, no improvement in investment, and big job losses.

But now, as the CMA deadline nears, a locomotive of big money is pushing hard to get this merger approved, fronted by a sponsored consultants’ report throwing smoke clouds into the evidence. That report has, in turn, just been slammed by a major telecoms research firm as a “Mickey Mouse” effort.

Who would lose from this merger? Pretty much anyone in the UK with a mobile contract: collectively, billions each year.

Who would gain?

Public records show it would mean a hefty drain of wealth out of the UK. Vodafone’s biggest shareholders are E& (based in Abu Dhabi;) the US-based firms Blackrock, Liberty Global and Morgan Stanley; and Norway’s Norges bank. Three is fully owned by Cayman-registered and Hong Kong-based CK Hutchison. Even these firms’ major “British” competitor EE, which would also gain from the reduction in competition from this merger, is owned by BT (ex British Telecom) whose biggest shareholders are Altice UK S.à r.l. (owned by a French-Israeli billionaire😉 T-Mobile holdings (owned by Germany’s Deutsche Telekom) and the US asset manager Blackrock.

The independent international evidence is unambiguous

This would be what is known as a “four-to-three merger” because although UK consumers can choose from at least 18 mobile service providers, only four are Mobile Network Operators (MNOs) which own and operate the mobile infrastructure and spectrum. (The others are consumer-facing organisations that piggy-back on the MNOs.) Post-merger, the UK would be left with only three MNOs: EE (owned by BT Group); O2 (owned by Liberty Global and Telefonica;) and Vodafone/Three.

There is extensive and unambiguous international evidence about the effect of mergers between MNOs, and particularly four-to-three mergers like this one — they mean higher prices for consumers, no increase in investment, reduced data use, swingeing job cuts — and shareholders make out like bandits.

For many years the UK would never have let a merger like this through — nor would the European Commission, as we’ll see — but there seems to be something in the wind this time: a feeling that big money senses a political opening this time. And the companies have marshalled some well-resourced bamboozlement to steamroller the objections.

So: what does the evidence say?

4-to-3 MNO mergers are bad news, everywhere

To give a first flavour of what happens in these kinds of mergers, see this class action suit in the United States, involving the disastrous T-Mobile Sprint merger, described as “one of the worst merger-enforcement mistakes in decades.” But there is more.

We published an extensive report in 2022 (updated in 2023) on the proposed Vodafone-Three merger, co-authored with Tommaso Valletti, the European Commission’s former Chief Competition Economist who has studied the telecoms markets for 25 years. Our reports have been widely cited, including in this UK parliamentary briefing and by the Unite trade union that is also vigorously opposing this merger.

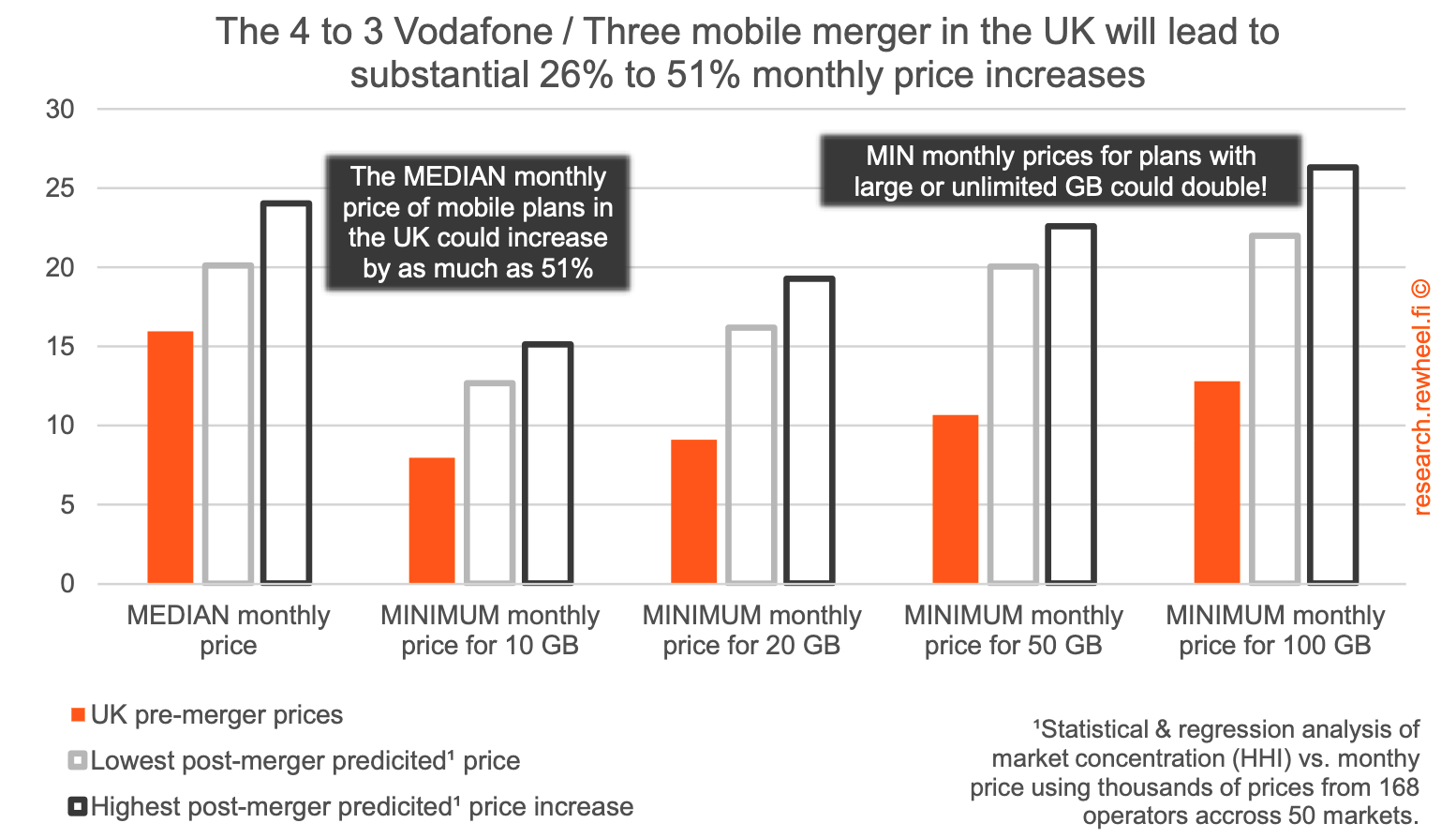

We looked at all sorts of academic and commercial evidence over many years, including several “meta” studies covering many countries. Our base-case conclusion, conservatively estimated, was that UK consumers should expect to see mobile prices rise by 15-50 percent on average if this merger goes ahead.

Separately, Unite said it expects Vodafone-Three could lead to 1,600 job cuts, and it also highlights extensive security threats given Three’s close relationship to the Chinese state.

Yet none of this has stopped the companies from making fantastic promises, as they did in evidence to the UK parliament in October 2023. In that hearing, our co-author Prof. Valletti testified (around 11:11:30 here):

“I have been studying mobile telephony for 25 years [and] I have heard this question [of the effect of such mergers] many times: from analogue to digital, from 2G to 3G, then from 3G to 4G. Every time, we hear ‘we need more consolidation in order to bring more investment.’ . . . I find no evidence that by consolidating there is more investment; instead I have found that every time there is a merger, prices go up.”

As has happened again and again, the two UK merging parties claim they need to merge to get enough scale to be viable. But as Valletti noted, not only do France and Italy, two countries with similar-sized markets to the UK’s, happily have four MNOs — but so does Slovakia – whose (less affluent) population is one-twelfth the size of the UK’s. [Update: in the original post we asserted that Cyprus has four MNOs; it has three plus a Mobile Virtual Network Operator, MVNO, which piggy-backs on an MNO.]

Consultancies blowing smoke around the evidence

So: all the independent evidence shows that mergers raise prices, but not investment or quality.

But this is not the evidence that the merging parties need. Enter the consultancies. In this case, a report by Compass Lexecon (CL,) a leading consultancy in competition circles, into four-to-three mergers.

Now, a bit of context. In April 2021 I interviewed Valletti for our newsletter, who described his extensive experience dealing with these consultancy firms.

“I live in the UK, and I see all these people in position of power coming from doing PPE [Politics, Philosophy and Economics] at Oxford University or similar. They are trained in the debating societies to argue anything, and the opposite, within 5 minutes. They are very eloquent. When I first came to the UK, I thought, as an academic, ‘how interesting, how witty, how intelligent!’ But it has actually been devastating. Because economic power will take exactly those kinds of people, then put them in front of a judge, or the Commission, and they will create smoke around an issue.”

He named Compass Lexecon (as did this article in ProPublica entitled “These Professors Make More Than a Thousand Bucks an Hour Peddling Mega-Mergers.“) In the case of CL’s new 4 to 3 report on telcos mergers there are 68 pages of evidence, attacking all those independent academic and other studies (including ours,) with plenty of this kind of impressive-looking stuff:

GIGO (Garbage In, Garbage Out)

This much evidence certainly would give any market regulator pause for thought. So: what to make of it?

A broadside riposte to the sponsored study

First, the authors admit their report was commissioned by Vodafone and Three: so it has an inbuilt pro-merger bias. The study declares that “the aim of the paper is to ensure a better evidence base for authorities in assessing whether proposed mergers are likely to benefit or harm consumers.” (That’s an interesting use of the word ‘better.’ Better for who?)

Thankfully, we have a delightfully frank public riposte, and new evidence, from the independent telecoms research firm Rewheel. Based on its data from thousands of monthly prices from 168 operators in 50 European and OECD countries it says plainly what it would expect from a V-3 merger:

“Consumers in the UK could see their monthly bills rise by 26% to 51% on average. Those that subscribe to mobile plans with large or unlimited data could see their monthly cost double.”

That’s close to our estimate. Here is a key Rewheel table:

Block this merger

What kind of competition are we talking about?

Competition is often healthy, and often harmful – but here it brings great benefits by stopping monopolising owners from fleecing consumers and workers, to the tune of many billions of pounds a year.

In many markets the presence of a “maverick” fourth MNO has been found to keep mobile prices low, as they offer discounts to gain market share (in the UK, the maverick is Three, which sells an unlimited data monthly package for £21, compared to the other MNOs’ £28-30 price range.)

Removing an MNO from a four-MNO market inevitably removes capacity as well as reduces data use while boosting prices: a classic unproductive price-gouging monopoly play. So for example, when the European Commission approved a four-to-three mobile merger in Italy between WIND and Hutchison Three by mandating an effective remedy – the upfront creation of a new fourth mobile operator – monthly prices “fell off a cliff” when the new MNO, Iliad, entered the market in 2018.

And two weeks ago the European Commission approved a deal with similar dynamics: a joint venture between Orange and MásMóvil in Spain, effectively leaving three independent MNOs; but they conditioned the deal on giving enough spectrum to a fourth operator, Digi, to allow it to build its own network. This fits the EU’s standard line that markets need at least four MNOs, and we hope for Spain’s sake that Digi flourishes and keeps prices low.

So there is a close relationship between competition and prices in mobile telecoms. Perhaps more surprisingly, Rewheel’s extensive research finds no link between mobile prices and:

the country general price level

GDP per capita, and/or disposable income

Population size or density

Land area

average mobile network download speed.

This is important, because the incumbents typically throw these other factors into the mix to try and undermine all those independent academic studies showing that these telecoms mergers are bad. What matters most for mobile prices, Rewheel argues, is the number and type of operators in the market: the state of competition.

“We consistently observed statistically significant uniformly positive linear correlations with very high confidence intervals between mobile prices and mobile market concentration.”

(They also found not just correlation, but that market concentration is causally linked with prices.)

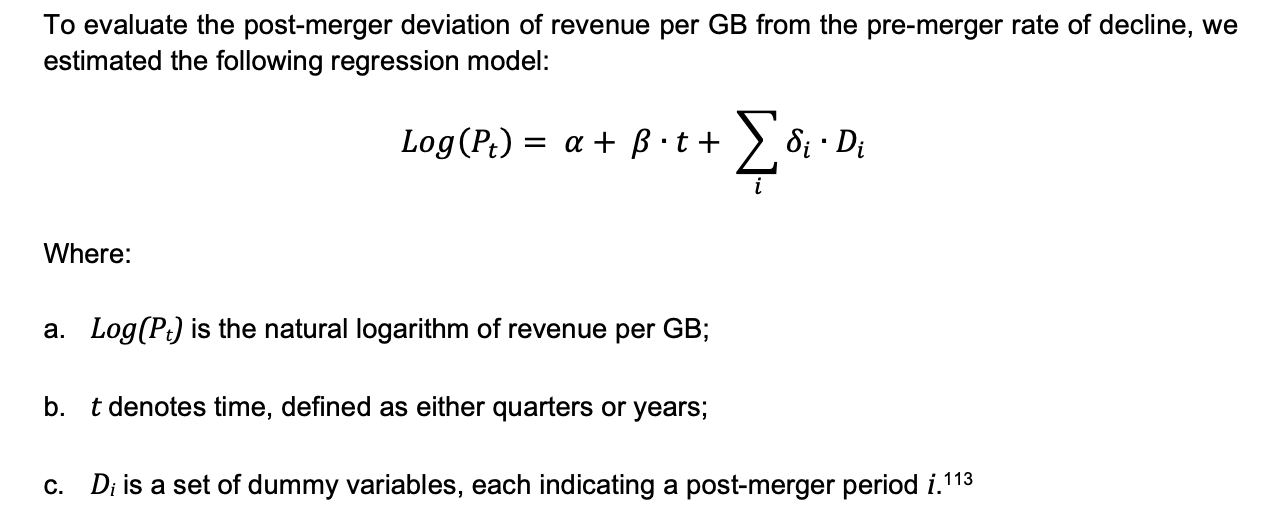

There are several other factors: for example, that post-merger price rises usually take a while to have effect, or that technological change means that mobile prices have generally and steadily been falling for decades masking the price effects.

Seeing through the smoke . . . to Jupiter’s orbit

Connoisseurs of smoke-blowing by the consultancy firms will especially enjoy the refreshingly robust section of Rewheel’s report entitled “Compass Lexecon’s dubious meta review” in which they dissect how this particular smokescreen works. Compass Lexecon a leading consultancy, cited two Rewheel studies but:

“Did Compass Lexecon review the full studies or only the public summaries? . . . Have they read Rewheel studies? . . . There are tens of other studies and research notes that Rewheel has carried out the last 12 years . . . Why did Compass Lexecon omit all those studies from its review?”

We spoke to Antonios Drossos, Managing Partner at Rewheel, who described Compass Lexecon’s article as “a Mickey Mouse report . . . shameful, and shameless.” Neither they nor the merging parties had licenced from Rewheel the two reports they cited, so he didn’t see how they could have read them.

Compass Lexecon uses so called ‘quality-adjusted’ prices, whose metric is “average revenue per gigabyte of data.” This has no relation to the actual price consumers pay every month: as technology improves, consumers use more and more data every year — so if you divide price by the increasing amount of data consumed, then mathematically this will show falling “quality-adjusted” prices (and this can happen even if consumers are paying more each month!)

There is more: but we’ll leave it by noting these feisty research questions:

“Compass Lexecon states that our analyses fail to control for factors that might influence both price and the level of concentration in a country. What are those mysterious factors that Compass Lexecon is referring to? . . . If Compass Lexecon is implying that Rewheel studies could not – with 100% certainty – rule out the possibility that other mysterious factors (Jupiter’s orbit?) might be the actual cause of higher mobile prices in concentrated mobile markets, we will be happy to test it if they can provide the reasonable causality hypothesis and the input data.”

In short, this merger needs to be blocked. Otherwise we’ll see wealth sucked straight out of consumers’ pockets and into the pockets of shareholders of these dominant firms based mostly in rich parts of London, overseas, and in offshore tax havens.

We’re delighted to see that just after the Rewheel study came out, the UK’s Business and Trade Committee wrote to the CMA urging it to move towards an in-depth investigation, warning that “significant doubts” had been raised about the merger. An in-depth investigation is hardly necessary: this merger must be blocked, according to a longstanding international consensus — and an ocean of evidence.

Indeed, it would be a shocking display of the force of big money if the CMA broke ranks and let this one through.

We are quietly confident that democracy will in this case prevail.