How Musicians Get Paid

At our recent event in Brussels we hosted Crispin Hunt, a former Chair of the UK’s Ivors Academy, which represents music creators. A successful songwriter himself, Hunt shocked the audience with this (at about 5.29):

“On one occasion, I counted 50 million views of a video for a song I’d written on Youtube, and I got paid £158 for that, over three years. I made more money busking in an afternoon in Bath.”

Your humble blogger recently chatted to a (less successful) musician friend, who reported that his latest royalty payment from Youtube / Google was . . . three cents.

Crispin Hunt at our recent Brussels event

Hunt continued (we have slightly trimmed his words, for clarity):

“There hasn’t been much of a conversation about the feudalism involved in having this much concentration of power. The traditional record contract is fundamentally feudal. You come to the market with your Intellectual Property (IP), and the music industry buys and owns all your IP, and gives you a small strip on which you can feed your family – but only after they artist has paid back every cent they’ve spent on you. It’s an ancient system.”

At the Balanced Economy Project we have heard the words “feudalism” and “serfdom” several times, first-hand, and unprompted, from small-scale retailers, musicians, farmers and others caught in the suffocating gravitational grip of monopolising giants. In music’s case, these giants include Sony Music, Universal, Warner Music Group, Spotify, and of course Youtube/Google, Amazon and Apple. Whether you consider musicians or farmers as workers, or as small businesses (often, they’re both), all of them – even giants like Taylor Swift – are caught in the grip of this power.

So, how do musicians get paid?

Well, we’re writing this today because there’s a lot in the news about the potential imminent implosion of Twitter, and we wanted to save a particular Twitter thread that goes a long way towards starting to answer this question. It’s from the (also successful) musician and campaigner Tom Gray, who succeeded hunt as Chair of the Ivors Academy.

Written in April 2020, in the thick of the Covid lockdowns, it begins like this:

Back to Gray’s Twitter thread:

2. We can’t expect our legislators or, more importantly, consumers to demand change on our behalves when it is such an annoyingly complex picture. However, everything is getting desperately clear.

3. The ways in which we make money are disappearing and the inequities of the recorded music business are being severely exposed. First of all, let’s consider touring as a means of income, well it’s gone. Done. Nada.

4. The next way artists, players and songwriters are rewarded is through a ‘Performance Royalty’ for writing and something else called ‘Equitable Remuneration’ for performance. That they appear to have the wrong names is one of the many ways in which this problem can prove obscure.

5. These royalties originate from licenses for your work to be played in public. TV stations, pubs, clubs, hairdressers and music venues in the UK will be very familiar with paying these licenses.

6. So what is about to happen? Businesses, shops etc will not be able to pay for those licenses in increasing numbers. Commercial TV stations will see their advertising revenues fall and ask to pay less for their broader performance licenses.

7. And with the collapse of touring, and the music venues not paying, the artists and writers will be doubly hit by the disappearance of the related royalties.

8. Which leaves the only remaining constant way that we get paid at all. The recorded music business. You’d imagine that what most people think of as ‘the music business’ would pay musicians right?

9. Well it turns out that if you subtract the other ways in which we’ve sought to pay rent, there really isn’t a lot of people making much money at all from a business that generates 10s of Billions in profits for the people who built the system.

10. Here are the money splits from streaming: Streaming company keeps 30%. The Recording gets 57%, the Song gets 13% (of which publishers get half). So that’s 6.5% that goes to the writers of which, on any song, there may be multiple.

11. What an artist earns from that 57% varies enormously. A few self-releasing and successful artists do very well out of this situation. But most artists labouring under Major Label contracts are unlikely to make as much as 50% of it. 20% in most cases.

12. When you consider how little the money earns from each stream (approx £0.005 per play), you need a lot of plays and any kind of money. We do not get a fair cut.

13. How did we get here? The recording industry used to have massive overheads. Shipping, packing, manufacture, marketing, distribution. These costs are still built in even though they do not objectively exist.

14. In fact, many labels still pay to artists based on 90% earnings because they hold back 10% for ‘breakages’ (when they used to pack vans with vinyl and there were inevitable casualties).

15. The other big question here is ‘what is streaming?’ The record business claims that it is reproduction and so all the money goes to them, but, even to the idle observer, much of what streaming does looks a lot more like broadcasting.

16. When your streaming service picks a song for you do you feel like you made a purchase or like you’re listening to the radio?

17. If accept the broadcast model for 50% of the streaming business, they would pay licenses and we’d get paid through performance royalties (both types described). The money would come straight through to artists/players/writers and not go through the (often vague) books of labels.

18. Getting to a place where the recording business pays fairly has to be in the interests of everyone involved. Maybe not the shareholders of Major Labels, but just about every single other individual in our profession.

19. It would begin to rebuild the lost middle class of the music industry and establish a healthy system that could weather these kinds of calamities.

20. We need to start the pressure now. We need to move on this. It’s not crass, it’s about survival and justice in an industry that has been able to play fast and loose for far too long with the talents of others for extraordinary profits.

Things have of course moved on a bit since Gray wrote that, but the essential structure remains unchanged.

Hunt notes, in particular, a market study underway by the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA,) whose interim report was little more than a whitewash, containing astonishingly blinkered headlines such as “The evidence suggests that the majors are not suppressing publishing revenues.”

(If you somehow still find this persuasive, read this blistering repudiation of the CMA’s approach by the Ivors Academy.) As Hunt put it:

“The study produced a depressing interim report, which identified all sorts of occasions where there was a dominant use of power: clearly the scales are tipped in favour of the larger players. But at the same time, because the consumer likes having Tower Records in their pocket with Spotify for £9.99 a month, the consumer loves it. [The CMA] completely failed to understand the effect.”

The music industry is a great case study into why the dominant Chicago-School “consumer welfare” ideology that has gripped competition authorities around the world has been so devastating. In prioritising the interests of consumers – in this case, “Tower Records in your pocket, with Spotify for £9.99 a month” – it has devastated the livelihoods of musicians.

It has also, surely, damaged music too.

And, beyond watery metaphors, there another factor to consider. In 2019, Hunt continued, two thirds of music on streaming services was “catalogue music” – old music. By 2022, this had risen to 85 percent. These trends are devastating innovation, creativity, small businesses, and led to an often cloying saccharine sameness, as many brilliant but impoverished musicians leave the industry.

A Berlin-based musician friend of the Balanced Economy Project said,

“I feel quite deflated. I don’t feel like putting my music out there because I know I’m going to get ripped off. . . It is just blatant theft.”

There is good news here, though. Regulators who have been cheerleaders for monopoly power are just now, as we’ve already shown, just starting to shift their thinking.

For example, the U.S. Department of Justice’s recent victory to block a proposed merger between Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster rested heavily on arguments – which had previously been discounted – that “monopsony power” – that is, buyer power – is bad for authors. (Your correspondent knows this personally: on signing a deal with Penguin Random House for his last book, his agent told him that had Penguin been separate from Random House, as they previously had been, he would most likely have got “quite a lot more” for his author’s advance.) A recent kerfuffle involving Taylor Swift and the monopolist Ticketmaster has prompted widespread outrage in the United States, and a fierce political reaction against Ticketmaster’s dominance.

So that’s the good news. But there is a long, long way to go.

Remember: £158 for 50 million views on Youtube.

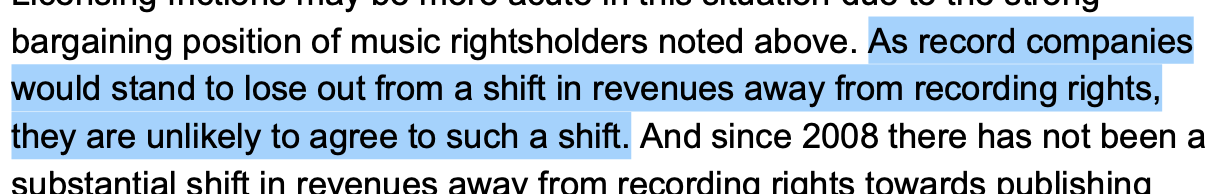

* Update: the final report has now been published, and it’s as bad as we feared. Take this, for instance:

What is a display of cowardice from the CMA, which has been so robust in other areas. The correct response goes like this: