From Public Services day, anti-monopoly can transform the day

Following the recent Public Services Day, it’s worth remembering the lessons from history: public services in an important sense pay for themselves. Public education or health, for example, are essential ingredients for any successful economy.

The countries that have most enthusiastically embraced austerity with extreme public spending cutbacks, to try and cut debt levels – are the ones that have suffered the most. A new study from the London School of Economics estimates that austerity cost the U.K. some 190,000 excess deaths from 2010-2019.

We have been told that ‘the money is not there’ for more public spending. But the money is there - and corporate power goes a long way towards explaining the blockage.

First, we estimated in 2022 that large firms in the UK Children’s Social Care sector were enjoying “excess profits” of £22,000 (€26,000) per child per year (a figure that the Competition and Markets Authority agreed with). So public money is poured into a crucial sector and then large private firms us extract a big slice of that public money for themselves, beyond any normal rate of return.

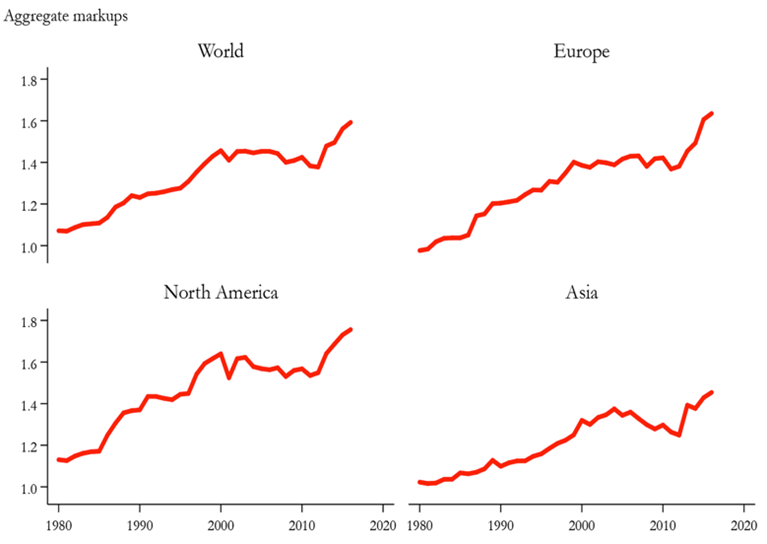

But this is emblematic of a much wider phenomenon in our economies: in sector after sector, dominant firms can use their market power capture a large and rising share of the economic surplus in that sector, leaving large numbers of others – small businesses, individuals – with less and less. This global trend is most easily seen through ‘markups’ – or price gouging: the prices that firms can charge for producing goods and services, relative to the costs of producing them.

Source: Taken, Not Earned (top graph) and The Profit Paradox (bottom graph)

Whether in farming, or in supermarkets, or in ride sharing, these firms are extracting the surpluses. So if you give public support for small farmers, for instance, the larger players that dominate our food systems may be able to extract that for themselves, leaving them no better off. Cory Doctorow likens this to the playground bully who steals other kids’ lunch money: if you give the other children more lunch money, it will just enrich the bullies - and the bullies may even campaign for parents to give their kids more. Better to tackle the bullying.

But that is not the only way in which ‘the money is there’. Dominant and monopolistic firms enjoy excessive profits, the fruits of these ‘markups’ (and other) tactics, and if it’s public services we’re interested in funding, then there’s an awful lot of tax that could be taken from them. Ideally, taxes are applied in ways that both raise significant revenues, and also reduce the market power in the system. The Balanced Economy Project outlined some of these in our “Tax and Monopoly Focus” with the Roosevelt Institute and Tax Justice network, in particular these two:

- Progressive Corporate Taxation. As the articles explain, there is good historical precedent for this. Basically, the idea is that the bigger the corporation, the higher the tax rate on corporate income.

- Excess profits taxes or windfall taxes. Again, these have a strong historical track record: they were used in the First and Second World Wars, with rates as high as 95 percent. They could be easily levied in, say, energy markets, serving three goals: raising revenue, curbing corporate power, and tackling climate change.

Beyond these, the tax system can push back on corporate power in other ways. For example:

- Taxes on “stock buybacks” (firms that channel profits into buying back their own shares to boost the share price, instead of investing it) could not only raise big sums for public services, but also boost investment rates and tackle market power.

- Another approach is financial transactions taxes, which could again tackle finance market power and raise revenues simultaneously.

- Digital Services Taxes. These hit the big tech firms in particular. DSTs are attractive because they are levied on sales, not profits: thus easier to administer than corporate income taxes, especially important for lower-income countries with weak tax authorities. A number of countries have adopted DSTs and the lobbyists are fighting hard against them, claiming (wrongly) that the tech firms will simply pass these taxes onto consumers. The size of the lobbying against DSTs suggests that these taxes will meaningfully impact the big tech firms (or else, why would they fund lobbyists to fight against them?)

- Wealth Taxes that hit billionaires in particular. A useful recent report from the Roosevelt Institute, bolstering our own research, shows the close interplay between billionaire wealth and corporate power. As Nico Lusiani of Roosevelt notes: “A billionaire income tax—especially if implemented alongside a global minimum wealth tax on billionaires—could reduce the financial incentives billionaire blockholders receive from monopoly-fueled share appreciation.”

There are in fact a plethora of other taxes – or the closure of tax loopholes – that can counteract excessive corporate power while raising revenue for public services and other good things. For example, new bipartisan legislation in the U.S. “to end the tax-free treatment for large acquisitive corporate reorganizations would reduce the capital gains tax breaks owners receive by landing merger deals.”

Finally, as we have shown elsewhere, corporate power fosters corruption – and in a profound sense is corrupt. If we want to achieve tax reform – or any other reform in the public interest, then we need to tackle corporate power to reduce the lobbying power arrayed against us.

The money is there. Now we just need to find the political courage to take it.