The dangerous fusion on big tech firms and the financial sector – what can be done?

If you’ve been watching the UEFA European football, you’ll have seen the endless advertisements for AliPay or AliExpress, parts of the Chinese big tech firm Ant Group, which is sponsoring the championships.

Alipay launched in China 20 years ago and now accounts for half of the country’s total mobile payments. Combined with rival big tech firm Tencent, they share 90 percent of the market.

An excellent new report from Finanzwende, now available in English, exposes how fast big tech firms are colonising financial and payments systems, how dangerous this will be, and offering solutions.

The spectacular speed with which China’s payments market ‘tipped’ to these giants suggests how fast it could happen beyond China. Services like Apple Pay and Google Pay are already proliferating around the world. Without government action to rein in these firms, they will use their privileges and dominance over rivals to capture these markets.

Big tech firms enjoy multiple advantages and feedback loops. They can leverage their huge troves of data and existing customer bases to launch their services directly, and almost frictionlessly, to consumers. These big tech firms can escape or circumvent essential financial regulations that constrain big banks; their lobbying power is now unrivalled; they have the financial firepower, market surveillance and dark patterns to kill rivals at will; and they can leverage their new financial data to grow their power in and into other domains.

The key problem here is not competition, or consumer interests: it is their sheer size and power. Big tech firms are already too big, and too powerful, and if they succeed in locking up payments, then move on to start entering other banking and finance functions, such as taking deposits and lending, their power will be ever more dangerous. Even Apple, which currently enjoys the most positive brand recognition of the big tech crowd, already poses tremendous dangers.

Concentrated economic power on this scale poses multiple generic threats to our societies. It undermines democracy, increases inequality, reduces overall prosperity, crushes small businesses, creates dangerous chokepoints stoking international tensions, harms workers, citizens, small businesses, increases corruption. Once in a monopoly position they increasingly milk us, and business users, with rising fees.

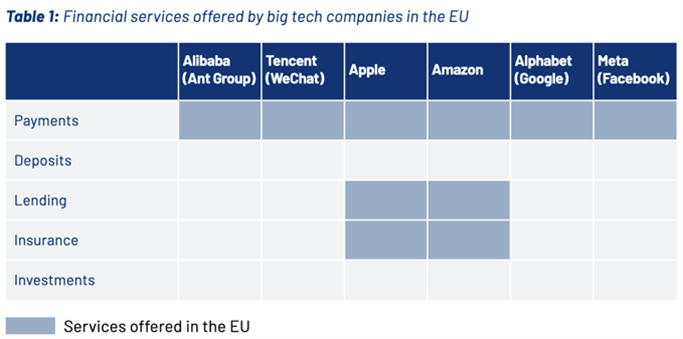

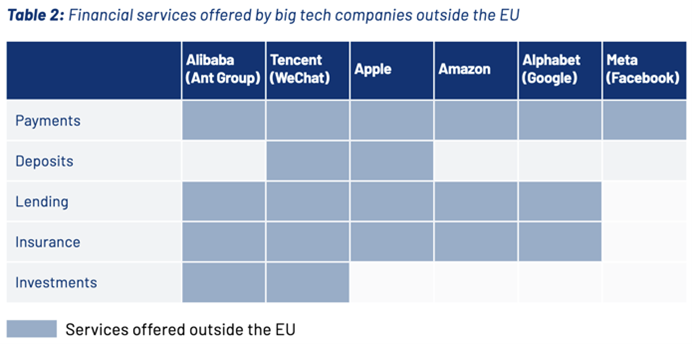

More positively, some countries or regions have been more successful than others in slowing the big tech surge into finance. Finanzwende has a useful pair of graphics to illustrate:

So whereas big tech firms have moved into payments, deposits, lending, insurance and investments in other parts of the world, they’ve been largely restricted to payments in the EU. This is a success: the EU has managed for now to contain the surge, up to a point.

But this clearly won’t be the end of the story, and no doubt the big tech firms will deploy their lobbying firepower to bludgeon their way into more and more of it. The key risk, as Finanzwende put it, is of firms that are too big to fail, and too interconnected to fail. One extreme scenario could have big tech firms, like the big banks, holding governments hostage in a big enough financial crisis, then milking taxpayers for billions in bailouts.

Financial regulation has evolved over many decades, with a few core goals beyond ensuring it provides the services economies need. Above all, regulation needs to protect individual and business users from exploitation, and to protect the stability of the financial system. When regulation fails, as we saw in the global financial crisis that erupted 17 years ago, the result is justified popular rage.

So our regulators must not let big tech firms surge into our financial systems. Finanzwende has a particular suggestion for how to stop this:

Those internal structural separations could perhaps go further still. Prohibitions or break-ups can ensure that big tech firms do not offer financial services in any areas that could pose risks to financial stability. Indeed, they can keep them out of financial services altogether. These firms are already far too big, and too powerful.

Big firms would tell us that this would disrupt shopping convenience, but these are small matters when compared to their multi-sided and extreme power. And in the real world, when you break any monopolist’s stranglehold in smart ways, the alternatives that emerge are always better than what the monopolists provide: the opposite of Enshittification.

For more on the looming big tech – big finance fusion, the Finanzwende report is here.