Workers versus consumers: an anti-monopoly approach

“EU consumers will have to pay higher prices to cover better rights for gig workers but the increases will not kill the industry’s business model, a senior Brussels official has predicted.”

This goes to the heart of a central puzzle at the heart of democratic and economic policy-making: how does one balance the competing interests of different groups of stakeholders?

The particular matter at hand is a draft European directive which, if it passes as currently drafted, will force ride-sharing and delivery companies like Uber or Deliveroo to offer more social protections to workers on their platforms.

The FT cites a warning by Anabel Díaz, head of Uber’s mobility division in Europe, that the move “would force the ride-hailing service to shut down in hundreds of cities across the EU if prices rose by up to 40 per cent.”

So here is that central tension: if Uber, say, has to pay its workers more, that may lead to higher prices, and consumers will suffer.

Workers versus consumers: Who should take priority?

It seems an impossible conundrum. But in fact there is a clear way through this impasse. We offer two answers: a general common-sense one, and a (common-sense) anti-monopoly one, both of which square the circle in ways that benefit both groups.

You don’t need tax breaks for air safety tests

A few years ago, the U.S. aircraft manufacturer Boeing suggested that it would only perform safety tests on its aircraft if it received tax breaks for doing so. This was patently nonsense, but it highlighted a common refrain from large corporations, that they “need” tax breaks in order to do certain things such as invest, or pay workers better.

These arguments, especially when it concerns dominant or highly profitable firms, are nearly always nonsense. These companies need tax breaks or free rein to exploit workers, in the same way that young children need ice cream.

When it comes to dominant and highly profitable firms, the real conflict is elsewhere: not between consumers and (say) workers, but between owners and the rest.

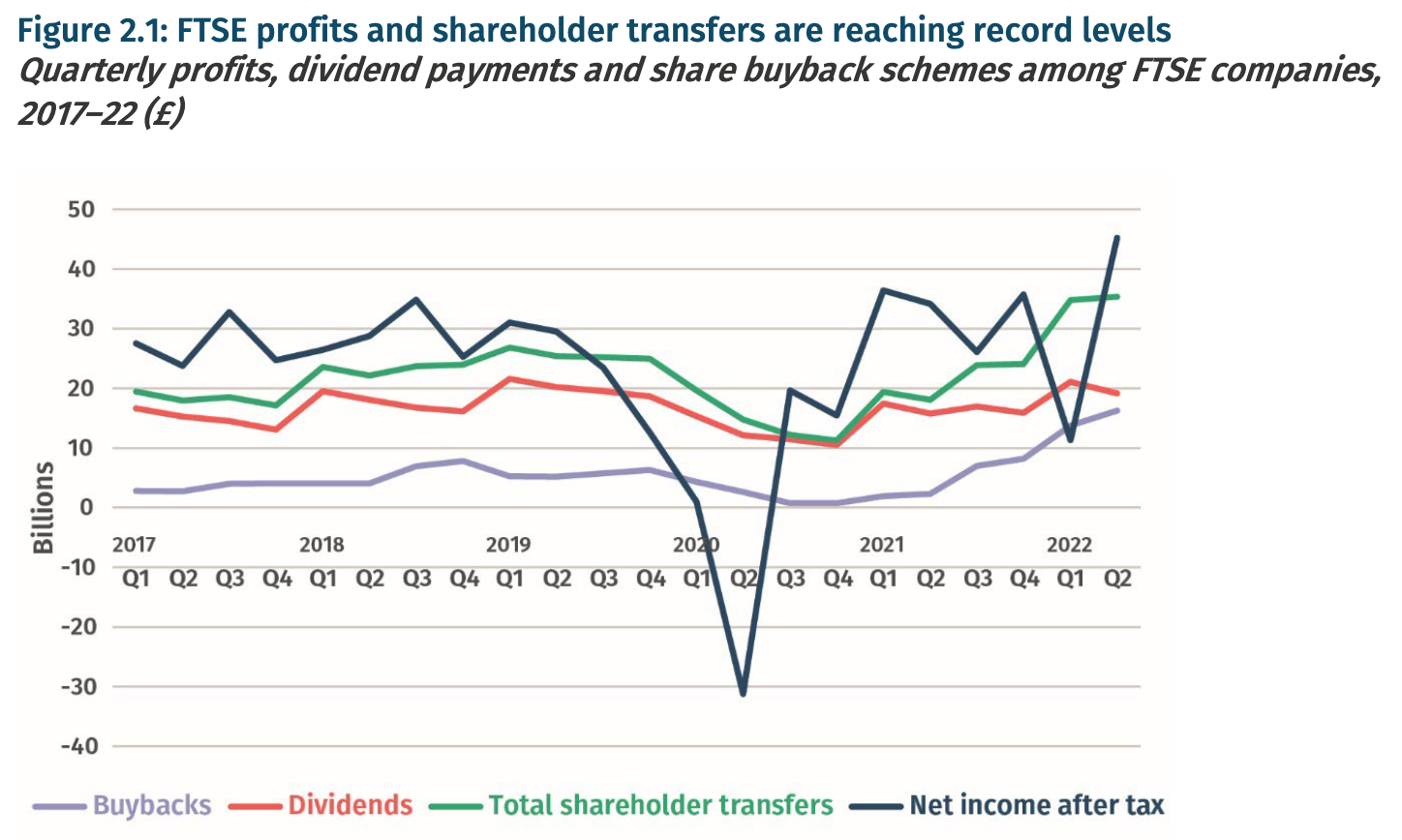

Specifically, large corporates are channelling much of their economic surpluses into dividends and buying back their own shares – buybacks – money that could go to other ends, such as paying workers better or investing. Dividends and buybacks reward existing shareholders and bosses (whose remuneration is usually tied to the share price) and are so unproductive that in some countries they used to be illegal.)

A report by the UK think tanks Common Wealth and IPPR notes the jarring contrast:

“While consumers face runaway prices and a historic squeeze in their real incomes, Britain’s biggest firms are transferring profits to their shareholders at record levels.”

Overall, European companies bought back €161 billion of their shares last year, instead of investing it, according to BNP Paribas.

These companies have plenty of slack to pay their workers more.

Workers versus consumers through the anti-monopoly lens

Anti-monopoly, it turns out, has other powerful insights to help reconcile the tension between different stakeholder groups, in the interests of both.

As we have long argued, the dominant economic model used by competition and antitrust authorities around the world is “consumer welfare”, an ideology that gained prominence first in Chicago in the 1970s and has since enthralled regulators, policy-makers and enforcers around the world.

Consumer welfare essentially tells market regulators to narrow down their field of enquiry to prioritise consumers, and the internal “efficiency” of corporations (measured narrowly). This has effectively airbrushed out of the equation the concerns of other stakeholders such as workers, citizens as rights-holders, the environment, taxpayers and more. It also hides the elephant in the room: power.

The idea is that large corporations generate economies of scale and scope that are the “efficiencies” that will then trickle down to consumers – and all will be well. Under this consumer welfare paradigm, regulators have waved through endless mergers, leading to steady consolidation of the corporate world (we will be producing new evidence on this in January.)

So in a fight between, say, Uber’s drivers (or workers) and its riders, consumer welfare comes down firmly on the side of riders, at the expense of workers.

We and many others have exposed the economic incoherence at the heart of the consumer welfare ideology – not least, that it has failed even on its own terms.

This failure is consistent with Economics 101, and even common knowledge: that if you let corporations become too big they will likely become monopolists – and monopolists jack up prices.

You can find the evidence of this in what economists call ‘markups”: the difference between input costs and prices. Look how these have risen, in the age of Consumer Welfare.

The left hand axis shows the ratio of prices to costs: a markup of 1.2 means prices are 20 percent above costs – so a rise from 1.2 to 1.6 means trebling of the markup.

These markups are then reflected in soaring profit margins, dividends, buybacks and so on.

Amazon is a case in point – as we explained in our last newsletter and short video – revealing how Amazon is likely to be contributing to higher prices across the economy, contrary to general perceptions. In the early years of its growth, Amazon built market share by providing things people want: now that it has enough power it is in, as FTC Chair Lina Khan put it, “extraction mode” – using a series of tricks to milk (among others) the independent businesses selling on its platform: now typically taking an astonishing half of seller revenue.

It looks like a similar story with Uber: as the analyst Hubert Horan explains: until the 2020 pandemic demand collapse, it took around 22% of gross customer payments; now its its take rate is 28-29%.

“This was not because Uber was providing an increasing portion of what customers valued. Uber simply figured out how to transfer over $1 billion in revenue per quarter from drivers to Uber shareholders.”

Uber’s business model reportedly involves using discriminatory algorithms for tailoring customer prices based on what they believe individual customers would be willing to pay, and tailoring payments to individual drivers so they are as low as possible to get them to accept trips.

“Uber is now just a much higher cost version of the traditional operators they vilified as an “evil taxi cartel”. Their fares are now higher than traditional taxis used to charge, they no longer offer a lot more cars in peak periods and they no longer serve neighborhoods throughout each city.”

It is true that Uber has had ‘profitability issues’ for some years, partly due to the particular economics of ride-sharing – so there may be less slack in the system than is the case for some dominant firms.

Still, we’re highly encouraged to see (in the FT article we began with) the words of Nicolas Schmit, the EU’s commissioner for jobs and social rights.

“In an economy you have consumers and producers of services. Our economy cannot just function on the basis of the advantage of the consumer,” he said. “It has to take into account the interest of the provider of the service. There has to be a balance.”

He also rejected Uber’s argument that it ‘needs’ to be able to exploit workers in order to stay in business, saying there was “no question that by better protecting the workers we will kill a model. No. We will adjust a model”.

When it comes to the current ride-sharing directive, the current consumer welfare frame pits workers against consumers, to the detriment of both.

A move away from the consumer welfare frame can open this binary view to a much richer vision, where shareholders and owners are crucial parts of the mix, who need to contribute their share, potentially to the benefit of consumers, workers, and others besides.